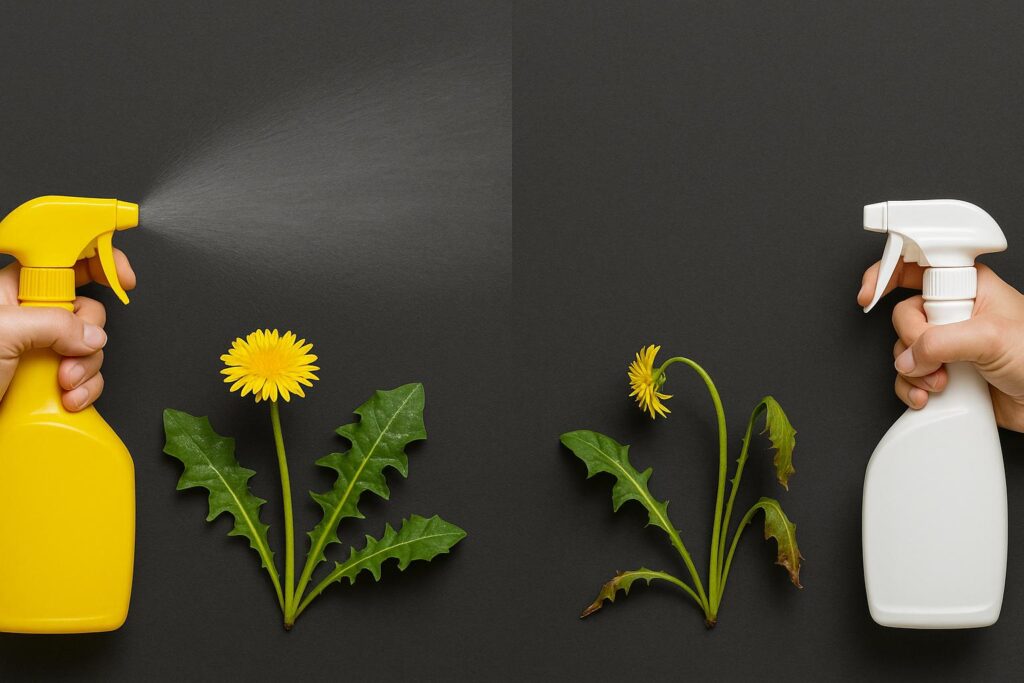

In the search for cleaner, safer, and more sustainable farming practices, herbicides are under scrutiny like never before. Among them, glyphosate stands out—not just for its widespread use but for the intense debates it continues to spark. On the other hand, a wave of biological herbicides is entering the market, fueled by innovations in microbial science and plant-based chemistry. The question farmers, agronomists, and regulators are asking now is simple: How does glyphosate truly compare to these new biological options?

Understanding the differences requires a closer look—not just at the science behind both approaches, but at how they behave in the field, what they cost, how they impact ecosystems, and how they fit into the larger movement toward regenerative agriculture.

The Fundamentals: What Sets Them Apart?

Glyphosate is a synthetic, broad-spectrum, systemic herbicide. It works by inhibiting a plant-specific enzyme (EPSP synthase), which is vital to the production of essential amino acids. This mode of action is highly effective across hundreds of weed species, including both annual and perennial varieties.

Biological herbicides, by contrast, are derived from naturally occurring substances—such as plant extracts, bacteria, or fungi. Instead of one uniform mode of action, they operate in diverse ways: some desiccate weed leaves, others alter cell membranes, while some disrupt photosynthesis or respiration pathways. These formulations are typically contact-only, not systemic, and their effectiveness varies by weed type and application timing.

Biologicals are newer, less standardized, and often marketed as safer for the environment. But that doesn’t automatically make them better. Effectiveness, scalability, and ease of integration still matter.

Efficacy in Real Conditions

Glyphosate’s edge has always been its reliability. It controls most weed types efficiently and translocates within plants, killing both roots and shoots. That makes it ideal for perennial weed control and situations where deep eradication is necessary.

Biological herbicides often require repeated applications and precise conditions to achieve similar control levels. For example, pelargonic acid (a fatty acid-based bioherbicide) can damage small annuals but struggles with mature perennials or grassy weeds. Similarly, essential oil-based sprays like clove or citric acid formulas work best on sunny days and lose potency with moisture.

This is one reason growers still prefer to buy Glycel Glyphosate 41% SL Herbicide not just because it’s cost-effective, but because it consistently delivers results in unpredictable weather, across crop rotations, and with minimal repeat spraying.

- Biologicals may require 2–3 applications to match one glyphosate treatment.

- Contact-only action limits their ability to handle deeply rooted or established weeds.

Regulatory Perspectives and Safety Narratives

One of the most widely discussed benefits of biological herbicides is their safety. Most have low toxicity profiles and degrade rapidly in the environment. They are often exempt from residue limits and don’t require long pre-harvest intervals. This has made them attractive for organic growers and for countries tightening pesticide regulations.

In contrast, glyphosate is subject to strict regulations. Although international scientific organizations, such as the European Food Safety Authority, insist that glyphosate is safe when used as prescribed, it has been the subject of lawsuits, restrictions, and prohibitions in several countries. More than agronomic science, popular and political perceptions are influencing its development.

Newer biologicals still need to demonstrate their scalability. Many have difficulties with shelf stability, efficacy testing, and registration. Biologicals are still gaining attention, in contrast to glyphosate, which has been proven by decades of research and standardized formulations.

Compatibility with Modern Farming Systems

Glyphosate is easily incorporated into conservation and no-till farming practices. It enhances water retention and reduces erosion by allowing farmers to control weeds without disturbing the soil. Additionally, it performs admirably in drone and sensor-based precision agriculture applications.

They are less adaptable than biologicals. They are not suitable for pre-plant or pre-emergent control due to their brief residual life. Although they typically supplement systemic herbicides rather than replace them, they can be very useful tools in an integrated pest management (IPM) approach.

It’s interesting to note that some microbial-based herbicides with promising systemic effects are now under development. One such product under trial in California uses a Streptomyces species to target grassy weeds by altering root zone activity. It is still in the early stages of development and is not currently a viable alternative to glyphosate on the market.

“Glyphosate is scalable. Biologicals are adaptable. The future of weed control probably needs both—working smarter, not just greener.”

Environmental Footprint: Nuance Over Narrative

Although it’s easy to portray this as a clean vs toxic issue, the truth is more nuanced. Compared to many other synthetic herbicides, glyphosate has a relatively benign environmental profile because it decomposes in soil, binds firmly to particles, and doesn’t readily leak into groundwater. Nonetheless, there are still legitimate worries regarding non-target impacts on aquatic life, beneficial insects, and microbial communities, especially when overuse occurs.

Conversely, biological herbicides are not impact-free but have less long-term hazards. Inappropriate use of high application rates can alter the soil pH or affect species that are not the intended target. If applied extensively, formulations containing vinegar or citric acid may eventually increase the soil’s salinity.

What matters more than the molecule is how it’s used. The overuse of anything—whether synthetic or natural—invites resistance, degradation, or unintended consequences.

Pricing, Access, and Cost Per Acre

One of the world’s most economical weed control solutions is still glyphosate. In many markets, generic formulas have reduced prices to as low as $2–4 per acre. It is cost-effective at scale due to its consistent dosage, wide range of applications, and shelf stability.

Because of their complicated production processes and shorter shelf lives, biological herbicides are generally substantially more expensive, sometimes costing $15 to $20 per acre or more. This premium may be justified for high-value crops such as greenhouse vegetables or berries. The calculation isn’t yet accurate for commodity grains, though.

Still, with consumer demand pushing for residue-free and regenerative practices, some farmers are willing to absorb higher costs for the reputational and market access benefits that come with “clean” inputs.

FAQs

- Are biological herbicides certified for organic use?

Many are, but not all. Always check with your certification body and product label for organic compliance. - Can I replace glyphosate entirely with biologicals?

That depends on your crop type, weed pressure, and operational scale. For many farms, biologicals complement glyphosate rather than replace it. - Do biological herbicides harm soil health?

Generally, no. Most have low environmental persistence. But excessive use of acidic or salt-heavy formulations could disrupt balance over time. - Is glyphosate being banned globally?

No, but it is under increasing regulatory review in many countries. Some regions have enacted restrictions or phasedowns, while others continue to support its use. - Which weeds do biological herbicides control best?

They’re most effective on small, broadleaf annuals in early growth stages. Perennials and grasses remain more challenging without systemic options.

Looking Forward: Convergence, Not Competition

What becomes clear is that this isn’t a winner-takes-all scenario. Glyphosate and biological herbicides serve different purposes, with distinct advantages and limitations. In 2025 and beyond, farmers aren’t being asked to choose one over the other—they’re being asked to integrate both with greater intelligence.

Biologicals will grow, change, and advance. Improved broad-spectrum, shelf-stable bioherbicides will be developed as more money and research is allocated to the fields of natural chemistry and microbiology. As part of a more intelligent system, glyphosate will likely assume more situation-specific, targeted, and low-dose functions.

Making decisions that are appropriate for the farm, the field, and the future will lead to success rather than adhering to tradition or following every new fad. What kills more quickly is no longer the only factor in weed control. What lasts longer is what matters.